AccelOpt: Democratizing AI Accelerator Programming with Self-Improving LLM Agents

January 17, 2026

The code for AccelOpt is open-source and available on GitHub: https://github.com/zhang677/AccelOpt. More details can be found in our paper. Accelopt is a follow-up to this work. Our next blog will be about extending AccelOpt to Triton.

AI accelerator kernels are hard to optimize

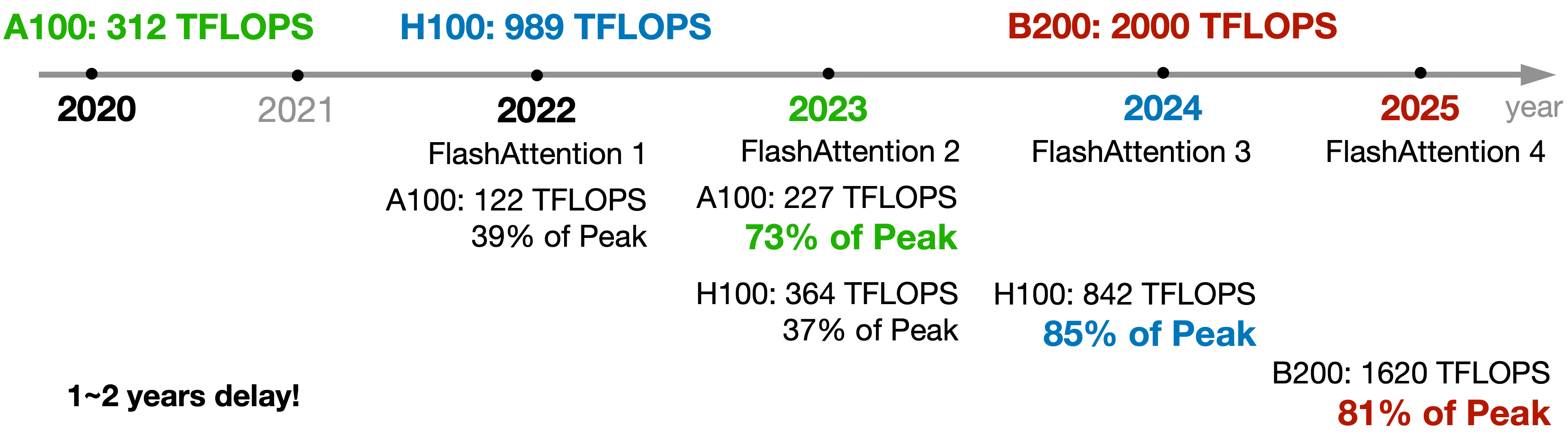

The unprecedented demand for compute power in the age of large models has prompted the rise of AI accelerators. However, their performance critically depends on the efficiency of kernels—the low-level implementations that determine how machine learning operators are mapped onto hardware resources. Suboptimal kernels can severely limit system performance and, when scaled to large deployments, result in substantial waste of compute and financial resources. Kernel optimization, however, is notoriously difficult and demanding, even for well-understood architectures like GPUs.

Can LLM-based systems autonomously navigate the kernel optimization space?

There are two primary challenges. First, LLM queries incur substantial computational costs, this exploration must be conducted strategically to balance comprehensive search space coverage with cost efficiency. Second, we aim to enable the LLM-based system to autonomously accumulate optimization insights during such explorations, allowing the system to progressively improve its capabilities over time without requiring manual intervention.

Solution: AccelOpt

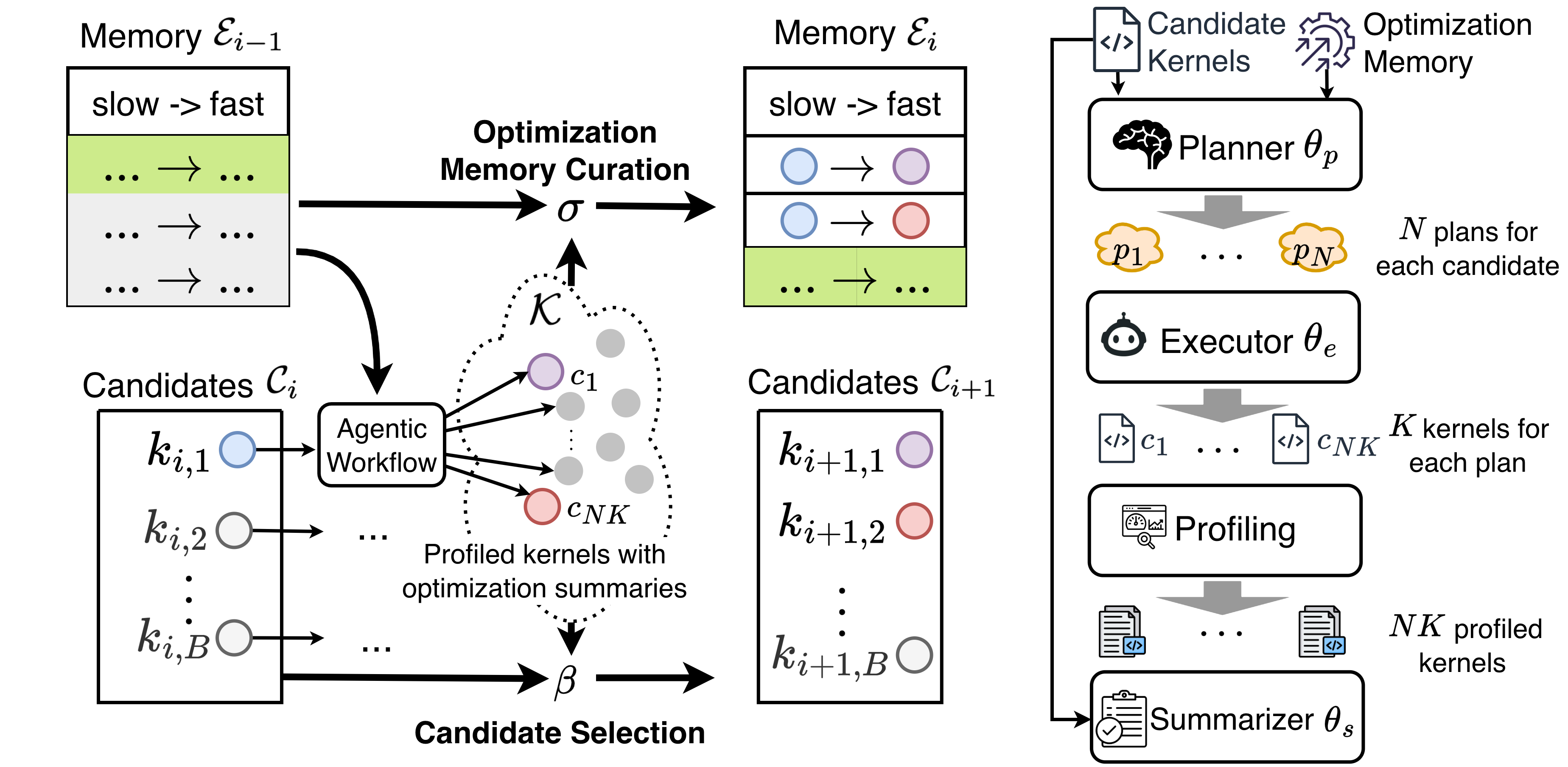

To tackle this challenging task, we propose AccelOpt, a self-improving LLM agentic system for kernel optimization on emerging AI accelerators that combines search with memory accumulation. Among the open-source systems we are aware of, AccelOpt is the first system that does not require expert-provided, hardware-specific optimization knowledge or predefined optimization recipes on emerging AI accelerators.

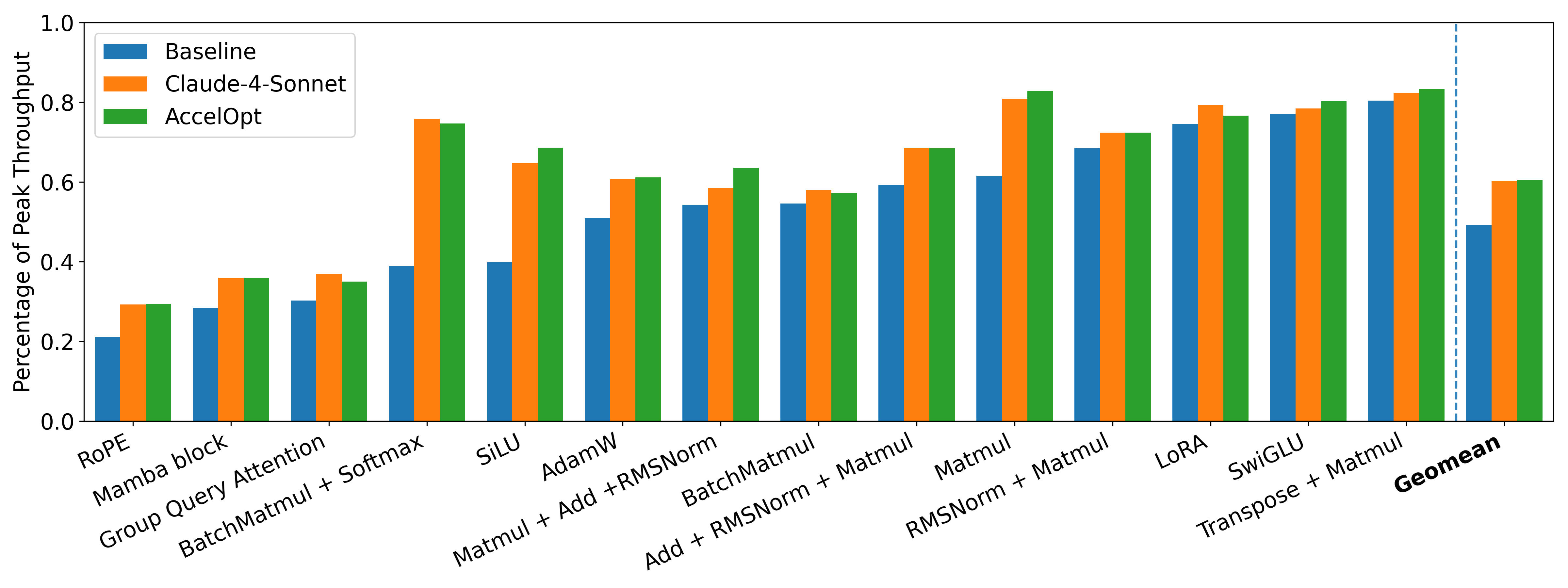

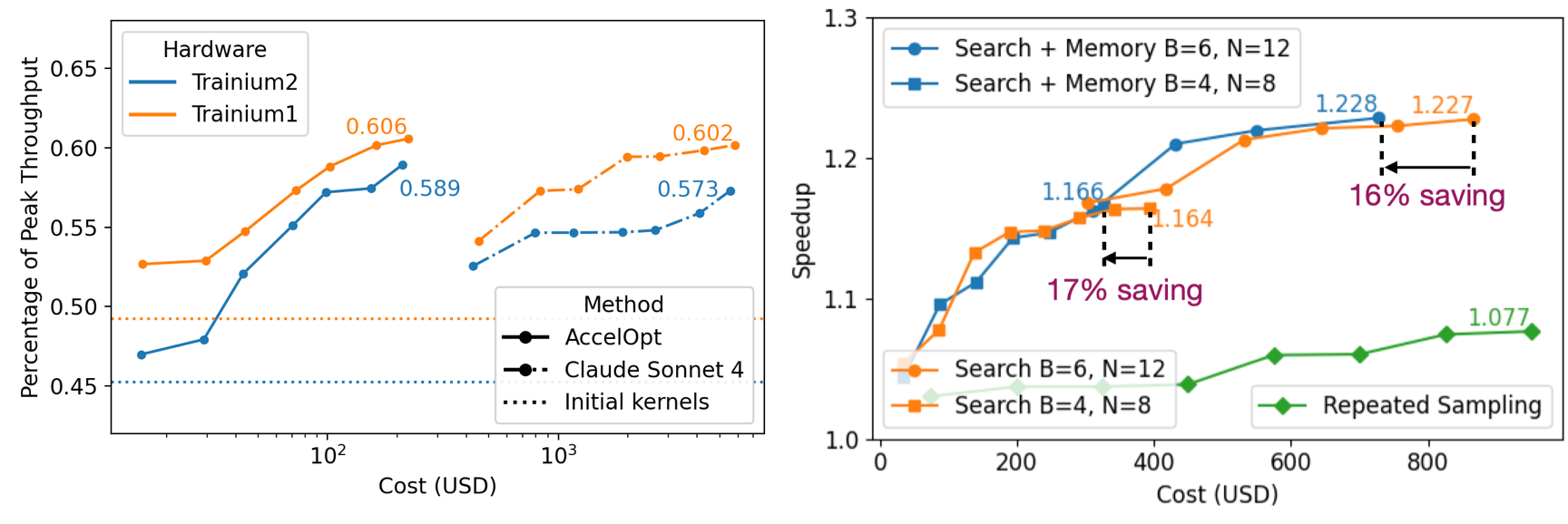

Real-world Kernel Challenge: NKIBench

We construct NKIBench, the first benchmark suite for NKI kernel optimization on Amazon Trainium, with all kernels derived from real-world LLM workloads. NKIBench measures kernel performance against theoretical peak hardware performance on Trainium, rather than relying solely on relative speedup metrics, which can be ambiguous due to different baseline choices. AccelOpt boosts the average percentage of peak throughput from 49% to 61% on Trainium 1 and from 45% to 59% on Trainium 2 for NKIBench kernels.

Enhancing Test-Time Scaling via Beam Search and Optimization Memory

AccelOpt leverages test-time scaling to unlock the potential of LLMs that may be under-trained for specialized tasks. It employs beam search to iteratively discover better kernels by building upon the best kernels of previous iterations. This aligns with AutoComp’s finding1. A key new finding of AccelOpt is the utility of optimization memory, which directs agents toward successful strategies. Similar to how RLVR improves pass@1 but not pass@n2, optimization memory reduces the cost of test-time scaling while achieving the same average performance. AccelOpt is highly cost-effective: using open-source models, it matches the kernel improvements of Claude Sonnet 4 while being 26× cheaper.

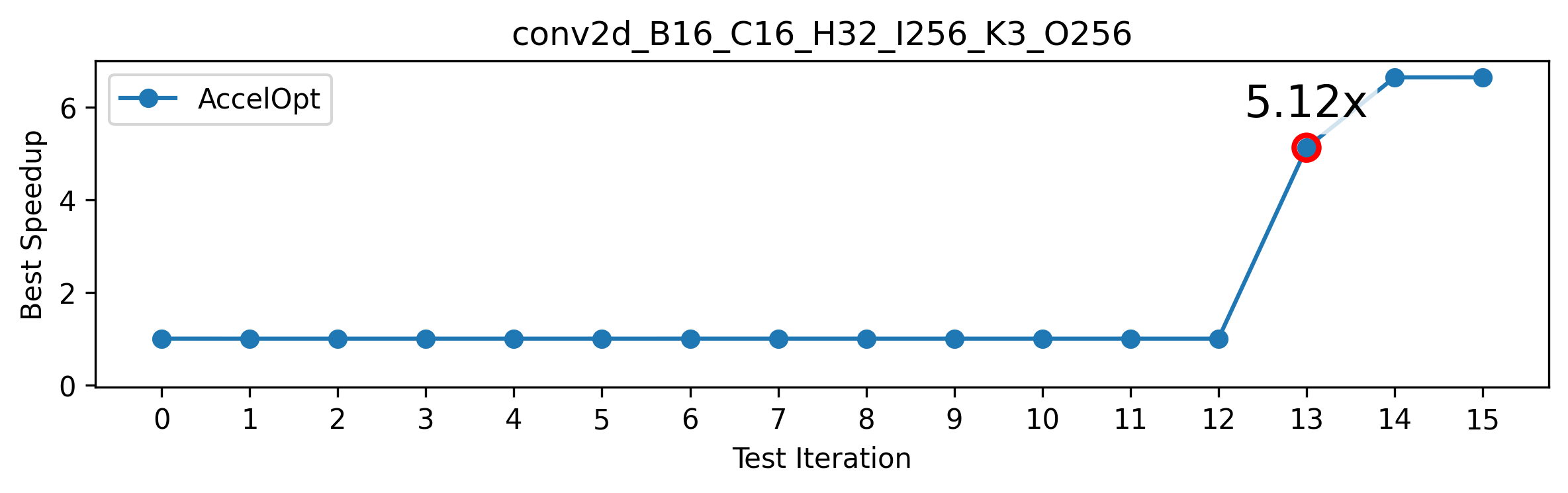

“Aha moment” and the Educational Impact

As a CA for Stanford’s CS149 (Parallel Computing), I leveraged AccelOpt to design problems for Assignment 4: Fused Conv+MaxPool on the Trainium2 Accelerator. During the 14th iteration of the optimization process, AccelOpt achieved a breakthrough by transforming a temporally sequential execution pattern into simultaneous spatial execution. This transformation resulted in a 5x speedup of last year’s reference Conv2D kernel on small-scale inputs.

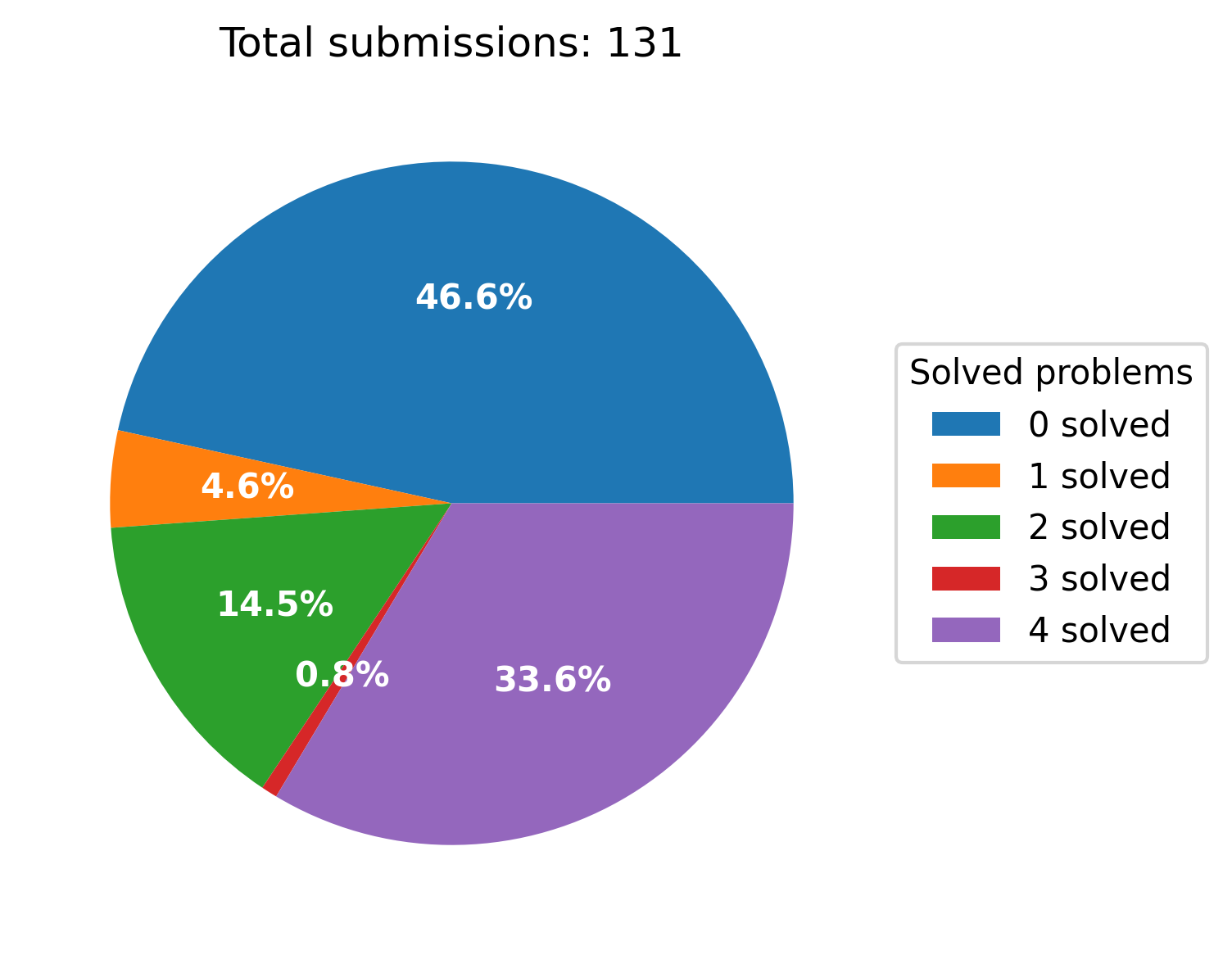

In collaboration with other CAs, we developed four extra-credit problems centered on this optimization technique. While the challenge was substantial, with approximately half of the class unable to complete it, 1/3 of the students successfully acquired this critical ‘spatial thinking’ skill, earning full extra credit.

This example underscores the generality of AccelOpt beyond NKIBench and highlights the educational impact of LLM-assisted kernel optimization.

Let the Agent Flow: Beyond Human Guidance

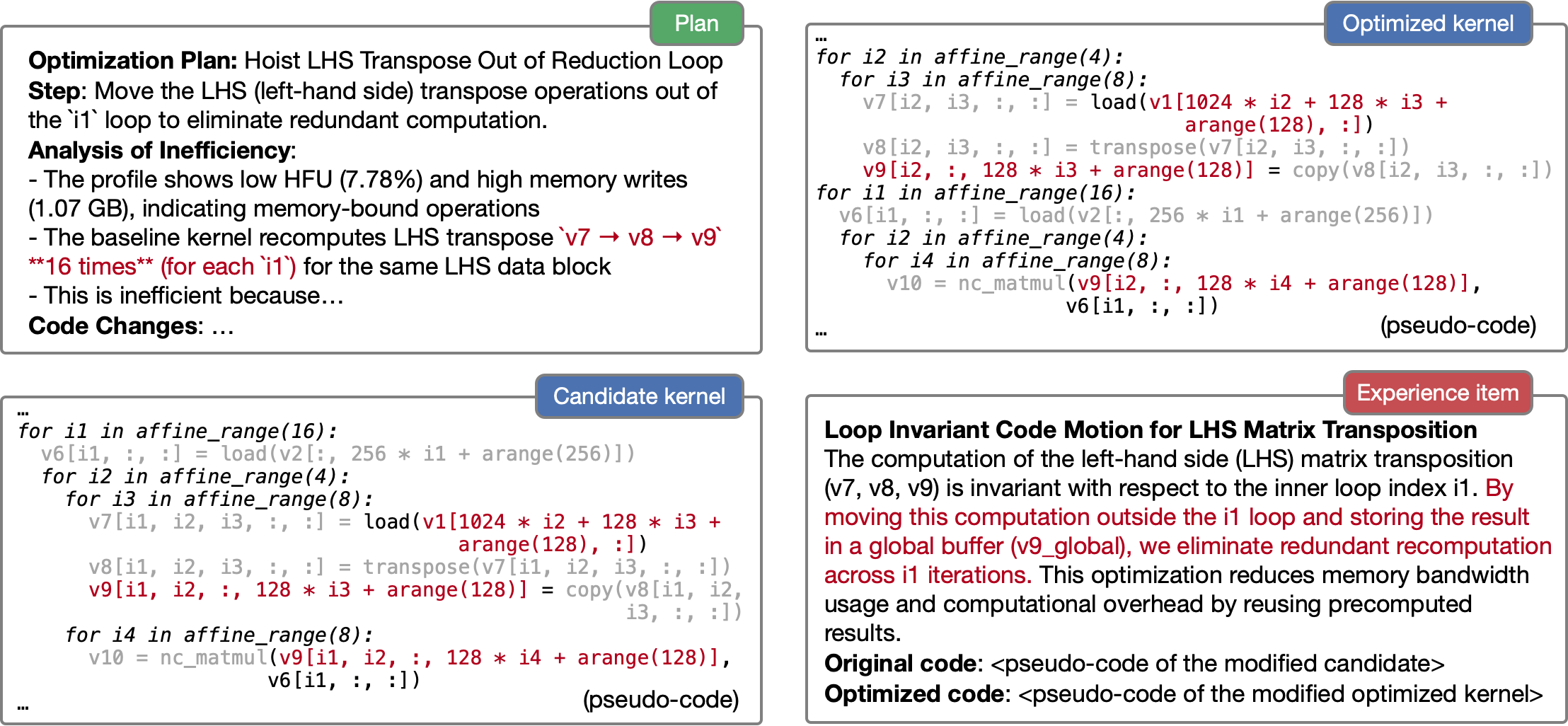

A notable finding of AccelOpt is that the base prompt does not need to include full syntax information for NKI—a relatively new architecture-specific programming language (ASPL) released in 2024. It is often assumed that LLMs must master the syntax of ASPLs before optimizing kernels3. However, as pointed out in this blog, many ASPLs’ syntax have a structural similarity to one another. Therefore, syntax is not the primary consideration; the priority is building a workflow that enables continuous improvement.

Within this continuous improvement workflow, AccelOpt demonstrates that human-crafted optimization guidance is unnecessary. It was previously assumed that designers needed to provide specific instructions, such as optimization plans for the LLM to select from1. Consequently, porting prompts from NKI to Triton simply involves replacing NKI-specific details with a few sentences about Triton. They can even share the same summarizer prompts. Interested readers can read the prompts for NKI and Triton.

Benchmarks as Environments for Self-Improvement

Kernel benchmarks have three distinct properties that distinguish them from traditional benchmarks with fixed answers (such as labels or solutions):

- Open-ended Optimization: Each problem remains technically “unsolved” because further optimization is always possible until the hardware’s theoretical roofline bound is reached.

- Hardware-Dependent Evaluation: Evaluating kernels requires directly running them on real hardware. With LLM inference and fine-tuning becoming standardized and optimized, the entire self-improvement process is often bottlenecked by kernel profiling.

- Production Readiness: The surrounding ML frameworks are mature, meaning optimized kernels can be deployed directly into production.

These properties indicate that kernel benchmarks environments must be scalable for new problems, parallelized to evaluate heavy sampling, and modular for “day-zero” integration. Developed concurrently with FlashInfer-Bench, NKIBench utilizes a similar interface that features structured storage for problems and kernels along with a distributed profiling service. This represents an advancement over traditional kernel benchmarks, such as KernelBench4, which consist only of a list of problems. By providing more than just a fixed repository of tasks, this new approach creates a comprehensive environment for the development of self-improving LLM agents.

How far is AccelOpt from Human Experts?

NKI Mamba. NKI tutorial provides three progressively faster human versions, reaching 28.4%, 30.1%, and 52.7% of peak throughput. Starting from the same baseline (28.4% of peak), AccelOpt autonomously improved the kernel to 54.6% of peak, which is 1.04x the best expert result (52.7%). Moreover, the generated kernel used a different loop order than the best human.

NKI RoPE. The initial RoPE kernel was adopted from nki-samples. NKI samples provide one version of RoPE (21.1% of peak). Starting from this version, AccelOpt improved performance to 29.6% of peak, a 1.4× speedup over the human reference.

These results demonstrate that AccelOpt can exceed expert-level performance in NKI. This stems from AccelOpt’s scalability: human experts optimize a handful of kernels sequentially, while AccelOpt can explore many in parallel. We uploaded all the kernels mentioned above here.

What about RL?

TL;DR: An effective training recipe has not yet been identified. We believe the potential of AccelOpt for data synthesis remains underexplored. Leveraging AccelOpt, we synthesized ~18k ‘slow-fast’ pairs through 16 iterations across 14 NKIBench problems. Additionally, we leveraged an in-house framework to produce 1k NKI kernels for training and 150 for evaluation. Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) was conducted using two distinct tasks: (1) slow-to-fast NKI kernel transformation and (2) Numpy-to-NKI program translation. Reinforcement Learning (RL) was then applied using GRPO via verl, trained on the 1k NKI kernel dataset. The reward function was designed to penalize empty outputs, compilation errors, and performance regressions, while incentivizing functional correctness and execution speedup. We evaluated four distinct recipes using a Best-of-5 sampling strategy. Metrics include functional correctness, the count of cases achieving a speedup ≥ 1 and the average speedup of them, and maximum speedup across the 150 evaluated problems.

Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-Instruct

| Recipe | Correct Cases | Cases with Speedup ≥ 1 | Avg. Speedup | Max Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base model | 126 / 150 | 39 / 150 | 1.022 | 1.194 |

| SFT-Slow-Fast | 127 / 150 | 31 / 150 | 1.034 | 1.179 |

| SFT-Slow-Fast-RL | 131 / 150 | 53 / 150 | 1.024 | 1.161 |

| SFT-Numpy-NKI | 125 / 150 | 75 / 150 | 1.029 | 1.135 |

| SFT-Numpy-NKI-RL | 132 / 150 | 52 / 150 | 1.018 | 1.149 |

DeepSeek-Coder-33B-Base-Instruct

| Recipe | Correct Cases | Cases with Speedup ≥ 1 | Avg. Speedup | Max Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base model | 105 / 150 | 26 / 150 | 1.025 | 1.095 |

| SFT-Slow-Fast | 70 / 150 | 66 / 150 | 1.040 | 1.172 |

| SFT-Slow-Fast-RL | 104 / 150 | 57 / 150 | 1.029 | 1.103 |

| SFT-Numpy-NKI | 105 / 150 | 49 / 150 | 1.032 | 1.210 |

| SFT-Numpy-NKI-RL | 108 / 150 | 67 / 150 | 1.025 | 1.152 |

RL infrastructure was initiated by Anjiang Wei, who also collected the first 1k+150 kernels, and implemented the Numpy-NKI recipes. Genghan Zhang later optimized the RL infrastructure, collected the 18k ‘slow-fast’ kernel pairs, and implemented the Slow-Fast recipes.

Fast-weight Engineering

Context engineering can be viewed as ‘fast-weight engineering’ because the context persists in the KV-cache, where it is referenced by every generated token much like static model weights. Workflows such as AccelOpt demonstrate that this is not merely ad-hoc manual prompting, but a systematic approach to fast-weight optimization. In a broader sense, just as back-propagation was designed to optimize weights, we are now seeking the most effective design for context. We are currently in an era reminiscent of the early days of neural networks, experimenting with diverse ‘weight engineering’ recipes to find what sticks. While ‘fast-weight’ may be an overloaded term in this context, I believe self-improving agents share a deep structural lineage with Test-Time Training (TTT). Both paradigms essentially treat inference not as a static forward pass, but as a dynamic optimization process where the model’s ‘state’—whether in the KV-cache or through local RNN state updates—adapts to the task (or sequence) at hand.

Acknowledgement

This work was a collaborative effort across several teams. I would like to thank our collaborators from Stanford University, AWS Neuron Science Team, and the University of Toronto: Shaowei Zhu, Anjiang Wei, Zhenyu Song, Allen Nie, Zhen Jia, Nandita Vijaykumar, Yida Wang, and Kunle Olukotun. Special thanks to Stanford CS149 instructors Kayvon Fatahalian and Kunle Olukotun, as well as the amazing CA team—particularly our “Assignment 4 gurus” Weixin Yu and Anthony Zhan—and the AWS support team for their essential role in the course.

References

- Hong, C., Bhatia, S., Cheung, A. and Shao, S., 2025, May. Autocomp: Llm-driven code optimization for tensor accelerators. In Machine Learning for Computer Architecture and Systems 2025. ↑

- Yue, Y., Chen, Z., Lu, R., Zhao, A., Wang, Z., Song, S. and Huang, G., 2025. Does reinforcement learning really incentivize reasoning capacity in llms beyond the base model? arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.13837. ↑

- Agrawal, L.A., Tan, S., Soylu, D., Ziems, N., Khare, R., Opsahl-Ong, K., Singhvi, A., Shandilya, H., Ryan, M.J., Jiang, M. and Potts, C., 2025. Gepa: Reflective prompt evolution can outperform reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.19457. ↑

- Ouyang, A., Guo, S., Arora, S., Zhang, A.L., Hu, W., Ré, C. and Mirhoseini, A., 2025. Kernelbench: Can llms write efficient gpu kernels?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.10517. ↑